In over twelve years of building distributed systems, ranging from high-frequency trading platforms to massive gaming portals, I have found that the most dangerous bugs are rarely the complex ones. They are the boring ones.

The most insidious bug in a mature codebase is Primitive Obsession.We define our complex worlds in terms of string, number, and boolean. To our compilers, a UserId is mathematically identical to a TransactionId. A StockPrice is just a number, exactly the same as a Temperature.

This leads to the classic "swapped argument" disaster:

// The compiler thinks this is perfectly fine.

// But you just sent money to the wrong person.

transfer(amount, toAddress, fromAddress); If your function signature is transfer(amount: number, from: string, to: string), you have effectively disabled the type system for those arguments. You are flying blind.

In this post, I am going to show you how to fix this using Branded Types and Zod. We are going to move from "trusting the developer" to "enforcing the architecture."

Table of Contents

- The Problem: TypeScript is Structural

- The Solution: The "Unique Symbol" Brand

- The Runtime Gatekeeper: Integrating Zod

- Putting It Together: The Architecture

- When Should You Use This?

- Final Thoughts

- References

The Problem: TypeScript is Structural

To solve this, we have to fight TypeScript’s nature. TypeScript uses a structural type system. If it looks like a duck, the compiler accepts it as a duck.

interface Admin { id: string; }

interface User { id: string; }

const admin: Admin = { id: "admin_1" };

const user: User = admin; // ✅ Valid in TypeScript!This is great for flexibility but terrible for domain modeling. We need Nominal Typing. We need a system where a User is distinct from an Admin because we said so, not just because they happen to have the same fields.

Since TypeScript does not support this natively, we have to lie to the compiler. It is a useful lie.

The Solution: The "Unique Symbol" Brand

I have seen many ways to implement Branded types, including classes and private fields. Most have runtime overhead or clutter your IntelliSense.

After years of iteration, this is the only pattern I recommend for production. It uses unique symbol to create a "private" property that exists only in the type system.

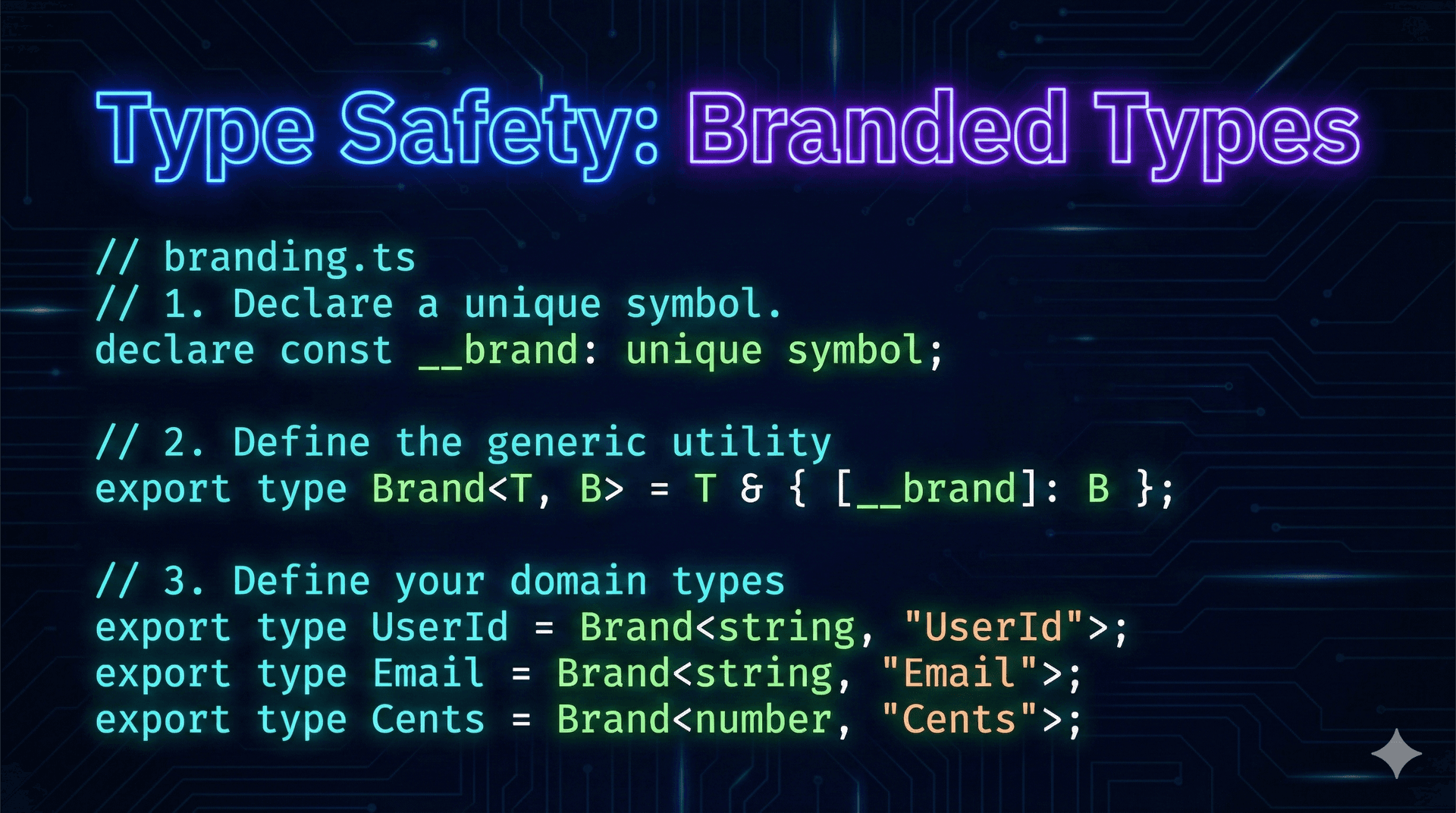

// branding.ts

// 1. Declare a unique symbol.

// This exists only in type space if we don't export the value.

declare const __brand: unique symbol;

// 2. Define the generic utility

export type Brand<T, B> = T & { [__brand]: B };

// 3. Define your domain types

export type UserId = Brand<string, "UserId">;

export type Email = Brand<string, "Email">;

export type Cents = Brand<number, "Cents">;This approach wins for three reasons. First, it has Zero Runtime Cost because the intersection vanishes after compilation. Second, it offers maximum safety because __brand is a unique symbol, so no other type can accidentally match it. Third, it keeps your runtime objects clean without ugly _type properties cluttering your console logs.

Now, if you try to assign a plain string to a UserId, TypeScript screams at you.

const id: UserId = "123";

// ❌ Error: Type 'string' is not assignable to type 'UserId'The Runtime Gatekeeper: Integrating Zod

This creates a new problem. If we cannot assign a string to a UserId, how do we ever create one?

You could manually cast it using as UserId, but that defeats the purpose. Manual casting is dangerous. We need a rigorous way to "bless" raw data into our trusted types.

This is where Zod shines. We use Zod to validate the structure at the I/O boundary. If it passes validation, we transform it into our brand.

The "Parse, Don't Validate" Pattern

I rarely use Zod's native .brand() method because it locks you into Zod's internal types. Instead, I use a custom transform pipeline.

import { z } from "zod";

import { UserId, Email } from "./types";

// The Gatekeeper

export const UserIdSchema = z.string()

.uuid() // 1. Validate structure first

.transform((val) => val as UserId); // 2. "Bless" the type

export const EmailSchema = z.string()

.email()

.toLowerCase() // Normalization is free here!

.transform((val) => val as Email);Why is as UserId safe here?

It is safe because it lives inside the Zod pipeline. We only cast the value after Zod has verified it is a valid UUID. We have encapsulated the "unsafe" operation inside a verified factory.

Putting It Together: The Architecture

Here is how this looks in a real Next.js or Node.js application.

1. The Domain Layer (Core)

Your business logic becomes self-documenting. It is impossible to call this function with an unvalidated string.

// domain/users.ts

import { UserId, Email } from "@/types";

export async function activateUser(id: UserId, email: Email) {

// If we are here, 'id' is guaranteed to be a valid UUID

// and 'email' is guaranteed to be a valid, lowercase email.

console.log(`Activating ${id}...`);

}2. The Input Layer (API/Actions)

This is the only place where raw strings exist.

// actions.ts

import { UserIdSchema, EmailSchema } from "@/schemas";

import { activateUser } from "@/domain/users";

export async function handleRequest(rawInput: unknown) {

const payload = z.object({

id: UserIdSchema,

email: EmailSchema,

}).safeParse(rawInput);

if (!payload.success) {

return { error: "Invalid data" };

}

// Payload.data.id is now typed as `UserId` automatically!

await activateUser(payload.data.id, payload.data.email);

}3. The Database Layer (Drizzle ORM)

If your database returns plain strings, you lose the safety chain. Drizzle ORM allows us to enforce brands at the schema level using $type.

// db/schema.ts

import { pgTable, text } from "drizzle-orm/pg-core";

import { UserId } from "@/types";

export const users = pgTable("users", {

// Tell Drizzle: "This column is a UserId, not just a string"

id: text("id").$type<UserId>().primaryKey(),

name: text("name"),

});Now, when you run db.select().from(users), the result automatically has id: UserId. The safety extends from your database all the way to your frontend components.

When Should You Use This?

I do not brand everything. Branding FirstName or Description is usually overkill because those are just text.

I use the "Identity & Criticality" rule. I apply brands to three specific categories.

- IDs:

UserId,OrderId,ProductId. Mixing these up is fatal to data integrity. - Units of Measure: Seconds, Milliseconds, Cents. NASA lost a Mars orbiter because of this error (https://www.simscale.com/blog/nasa-mars-climate-orbiter-metric/), and you might just lose a customer.

- Sensitive Data:

HashedPassword,SanitizedHtml. This prevents you from accidentally rendering a password to the UI.

Final Thoughts

Branded Types represent more than just a clever TypeScript hack. They are a declaration of intent. They allow us to write code that aligns with Domain-Driven Design, where our function signatures speak the language of the business rather than the language of the CPU.

By combining the compile-time guarantees of Branded Types with the runtime verification of Zod, you create a defense-in-depth strategy that eliminates entire categories of bugs before they ever reach production.

Stop passing strings. Start passing meaning.